Looking to launch your games in China and grow your user base? Leave us a message.

Despite the Chinese release freeze, 2018 was another headline year for mobile games. From negligible revenues in 2010, it’s now the largest – actually the majority – sector of the +$130 billion annual global game market, and remains the fastest-growing.

Yet for the game developers behind these headlines, the winner-takes-all business model behind app store distribution has resulted in an increasingly stark segmentation of have and have-nots.

And that’s something which has been demonstrated in recent years when considering how the value of mobile game developers has changed, at least as reflected in terms of corporate activity such as acquisitions and IPOs.

Balancing risk with reward

As with any industry, the truly eye-watering deals happen early in a cycle, when there is maximum uncertainty about how large a market could be and which companies will be the winners.

For example, now long forgotten but back in the pre-smartphone days of 2005, EA spent $680 million (now worth around $900 million) buying Nasdaq-floated mobile game publisher JAMDAT.

Its sales at the time were estimated at around $80 million. In retrospect, the deal is perhaps most charitably described as speculative, although JAMDAT was the foundation on which EA Mobile’s early success was built.

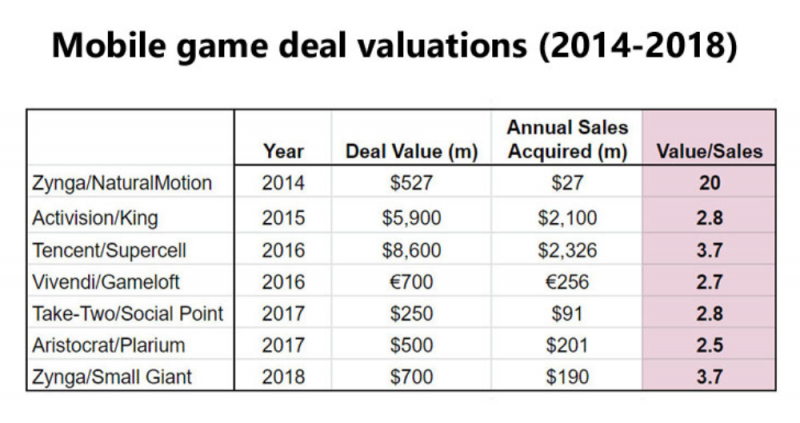

Less easy to constructively criticize is the $527 million Zynga spent buying UK studio NaturalMotion in late 2014. It had just successfully launched its CSR Racing game and was working on strategy title Dawn of Titans. However, NaturalMotion’s annual revenue at the time was less than $30 million, and not all of that was from mobile games.

On that basis, Zynga paid around 20 times NaturalMotion’s annual sales compared to the 9 times EA paid for JAMDAT.

(Technically the prefered ratio to use is acquisition price compared to a company’s profits because profits are free cash that can be reinvested. But in most cases, profitability is kept a secret so revenue data is what we’re left to work with. For that reason, the calculations in this article inherently assume mentioned companies have a similar profit margin.)

But to cut Zynga some slack over NaturalMotion, 2014 was a much more uncertain time for the mobile game industry. Thanks to an explosion in smartphone sales and frictionless distribution from the App Store and Google Play, the sector had just started its hockey stick growth trajectory.

Games such as Clash of Clans, Game of War and Puzzle & Dragons were well on their way to becoming billion dollar sellers.

In that context, NaturalMotion was expensive but with $900 million in the bank, Zynga wasn’t betting the farm on that one deal. Indeed, the US company has been the most active dealmaker over the past decade, closing over ten sizeable acquisitions.

Looking to launch your games in China and grow your user base? Leave us a message.

Finding balance

And its most recent acquisition demonstrates how deal dynamics have changed in the past four years.

In late 2018, Zynga bought 80% of Small Giant Games for $560 million, valuing the Finnish developer at $700 million. A bigger deal than NaturalMotion, nevertheless thanks to the success of its game Empires & Puzzle, Small Giant could point to a very different financial momentum.

With annualized sales estimated at around $190 million and still growing strongly, Zynga’s valuation of Small Giant Games isn’t cheap. But it’s by no means expensive either.

Indeed as this simple table demonstrates, since 2015 the valuation of companies versus their sales has been in the range 2.5 to 3.7 times, no matter whether they’re been $100 million deals or $9 billion deals.

(NB: Assuming a 25% profit margin, these ratios would roughly translate to a range of company valuations of 10 to 15 times profits.)

Hence, given that the mobile games market can now be considered mature, especially in the west, any developer demonstrating it has titles that are already profitable and have the potential to scale further is in a very strong position.

Similarly, for companies such as Zynga, which have access to cash, shares and other financing – prior to the deal Zynga had $420 million cash and now has a $200 million bank credit line – such deals provide a low-risk option to quickly growing revenue.

Certainly, the chances of any developer launching the next Empires & Puzzles-class hit are now tiny to disappearing. And that means the value of the vast majority of mobile game developers, especially those without a strong track record, has reduced accordingly.

Going public

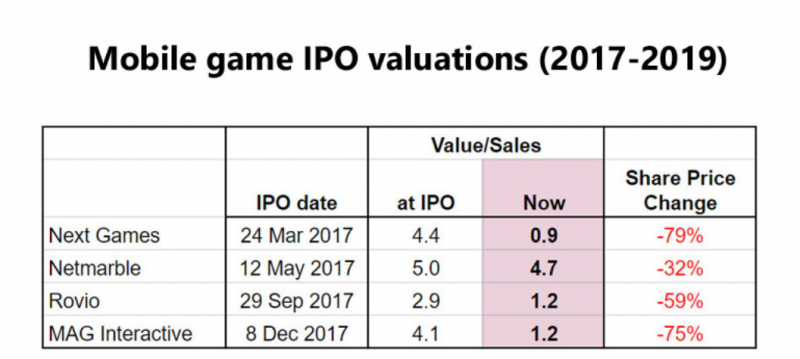

The acquisitions of mobile game companies by other companies is only one way of generating a valuation, however. A growing trend in recent years has been for companies, even fairly small ones, to sell their shares publicly on stock exchanges. Indeed, in the mobile game sector, it’s expected US publishers such as Scopely and Jam City are gearing up to IPO in 2019, so it’s worth looking back at some previous experiences.

2017 was a particularly busy year for such activity with four companies – ranging from the very large to the small – floating. The very large was Korean publisher Netmarble, which floated on an $11 billion valuation, while Swedish indie Mag Interactive was valued at around $130 million.

Interestingly valuing these companies at their IPO share price demonstrates a very similar trend to the deals previously discussed; the range being a reasonable 2.9 for Rovio up to 5 for Netmarble.

The difference is that while corporate M&A activity sees the buyer and selling negotiating between themselves to make a deal happen – and of course we never hear about the deals that don’t – once a company is floated on a stock exchange, its value is set daily by market forces.

In this context, all four of the mobile game companies that floated in 2017 have suffered. Each has experienced specific headwinds – Rovio’s failure to educate investors about its UA strategy being a notable example. But more generally they’ve also found themselves operating in a competitive market with increasingly expensive costs.

This has been particularly difficult for smaller companies as can be seen from the performance of Next Games and Mag Interactive. As with Netmarble, both have experienced declining sales since they floated but their small scale means compared to Netmarble means they’ve been hit harder by market sentiment.

The result is compared to 2017, all four companies have seen their value both in terms of market capitalization and value relative to sales reduced.

Which reminds us of another truism of deal-making: the most important thing is always timing.

" alt="">

" alt="">